Surface treatment in the form of Corona is a well-known and acknowledged part of the printing, converting, and laminating sectors of the industry, – but it has an even more fundamental part to play in the extrusion process. Giuseppe Rossi is Vetaphone’s specialist in this sector and explained the need for the process and how technology is responding to changes in market demand.

Why is surface treatment so important in the extrusion process?

It’s not so much important in the process itself, as afterwards. To ensure good adhesion of the inks and lacquers during downstream converting processes, the molecular structure of the film surface needs to be modified, and it needs to be done immediately after the cooling phase of the melt before the polymer is completely post-crystallised. By applying the corona charge at this point to the top layer (to 1-micron deep), we can break the molecular chains and add more oxygen. This alters the surface tension and improves adhesion. The longer you leave it before treatment, the more difficult the molecular chains are to break – in fact, it’s often impossible, so timing is critical.

Are there different requirements for blown and cast film extrusion?

Blown film is the more common use for corona treatment. Because of the high incidence of LDPE in this process and the relatively slow production speed, compared with cast extrusion or any of the converting processes, the corona system requires only low energy to achieve a good result. The technology in this sector is well consolidated and mature, and with good control allows consistently high-quality film to be produced and treated.

Cast film is a far more demanding process because the PP material and higher line speeds require a more complex corona system layout. Even a single-sided treater (unlike the double-sided in blown extrusion) will typically need higher power, a cooled backing roller, direct drive and a nip roller – effectively a proper pull set up.

There is a third type of extrusion that applies to Bioriented Cast Films like BOPP, BOPET, BOPA, where the width of the line and the high output demands that the corona unit is contained within the extruder.

Are the requirements different depending on the material being extruded?

Yes, they are. It very much depends on the material and its intended use. How it will be converted after manufacture brings a number of variables into the equation. For a start, every polymer has its own starting dyne level – that’s its ability to adhere inks and lacquers. Some materials, like PVC or PA, require very little power to surface treat to the correct dyne level – PE requires a little more power, and PP is notoriously the most difficult to treat. You also need to allow for the additives mixed in with the polymers, because these can significantly affect the level of corona treatment needed, and the power consumed.

With all these considerations, what benefit does Vetaphone technology offer extruders?

It’s all down to good design, which has been fundamental to Vetaphone equipment dating back to the beginning in the 1950s when the company invented and pioneered what has become known as corona treatment. Two principles stand out: simplicity and high efficiency. By designing and building a unit that is user friendly, Vetaphone makes cleaning and setting easy with its quick-change cartridge system. If you back this up with high-efficiency generators that use the patented resonant circuit, you have the capability of delivering 96% of input power direct to the electrodes. This reduces the heat level, which is an obvious advantage when you are handling lightweight extruded films. There are other factors such as the refined level of control available through our iCC7 interface – but essentially, simplicity and high efficiency are the main benefits here.

We refer to surface treatment as corona – is there an application for plasma in this sector?

Not really – but you need to understand the difference between the two processes to know why. Plasma is not a replacement for Corona – it’s a different way of treating the surface of certain substrates that require a chemical as well as a physical treatment. It has more of an application in specialised offline converting procedures where the chemical structure of the material is very complex and requires a very high dyne level that corona cannot achieve. It requires a controlled environment and the use of different dopant gases – and is significantly more expensive than corona, so used in specialist situations only.

How has the extrusion market changed in recent years?

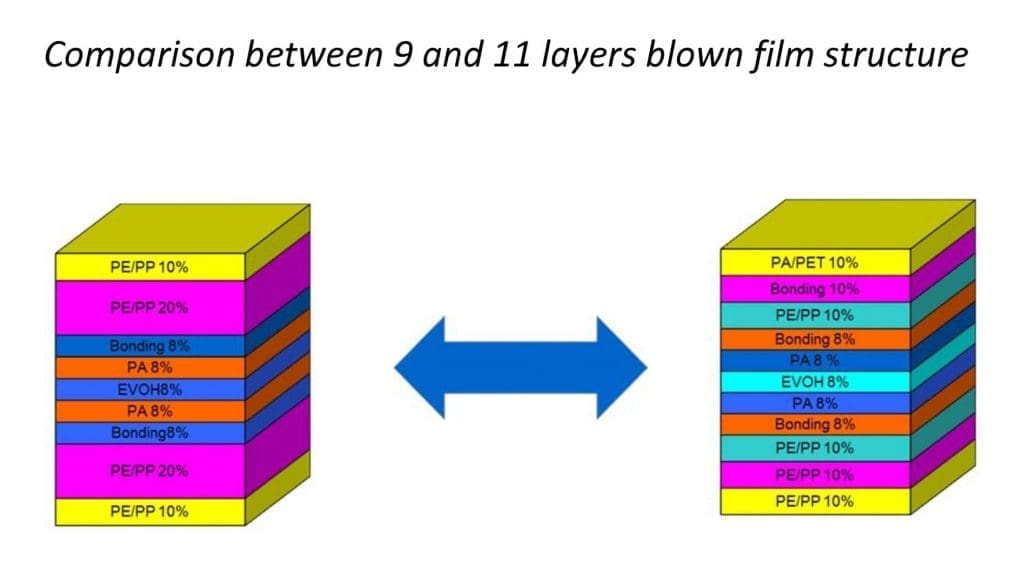

It’s changed because the markets it’s supplying have changed. If you go back 20 years, the majority of films being extruded were up to five layers for use in the technical and industrial packaging sectors. Nowadays, with the emphasis more on meeting the ever-growing demands of the food, pharmaceutical and hygiene markets, packaging with up to 13 multi layers are far more common, and the product is required to meet a variety of demands. These include freshness, protection and recycling, and pose complex problems for manufacturers. Take the current dramatic situation with the COVID19 pandemic, which is highlighting the vital role that packaging plays in our daily lives and welfare. Situations like this drive demand for new technology and future applications that enhance the value of so-called ‘clever’ packaging. And, it all starts with extrusion!

Plastic packaging seems to be ‘Public Enemy No 1’ right now – what steps is the extrusion market taking to become more environmentally friendly?

Despite public opinion to the contrary, plastic packaging has a very low carbon footprint as far as manufacturing is concerned. But, mindful of its image, and the need to take its responsibilities seriously, I’d say that there are two ways in which extrusion is helping to ‘go greener’. The first is in downgauging the packaging by using new resins that allow for less volume of plastic to be used. This helps with problems like shelf-life and hygiene where the extrusion of a special material removes the need for several laminated and heterogenous substrates. The second is the way the industry is working to simplify the structure of packaging by using compatible resins to improve recyclability as part of the circular economy. It’s not the manufacture of plastic that is the problem – it’s how it’s disposed of after use that is the real issue.

Is this the next big challenge for the industry?

Yes, no question about it. As we all know, the EU has set very ambitious targets for reducing the production of plastic and increasing the level of recycling. But it’s very difficult to equate the oxygen barrier demand with the sole use of Polyolefin resins. One solution is to extrude bioriented blown films, so-called triple bubble technology, where the orientation of the molecules dramatically improves the properties of the standard resins used in general purpose packaging. The oxygen barrier will not be as good as that offered by EVOH or PA, but good enough to replace much of the packaging where they are currently being used. There are no simple solutions, but demand drives R&D and gives birth to new technology – extrusion is no different in that respect.